The reasons for Dr. Ballard and Team’s success in finding the R.M.S. Titanic in September 1985 are numerous, but one factor stands out: the shipwreck’s debris field. Unlike a corollary accident investigation like a train derailment or airplane crash, finding a shipwreck on the ocean floor is like finding the proverbial needle in a haystack.

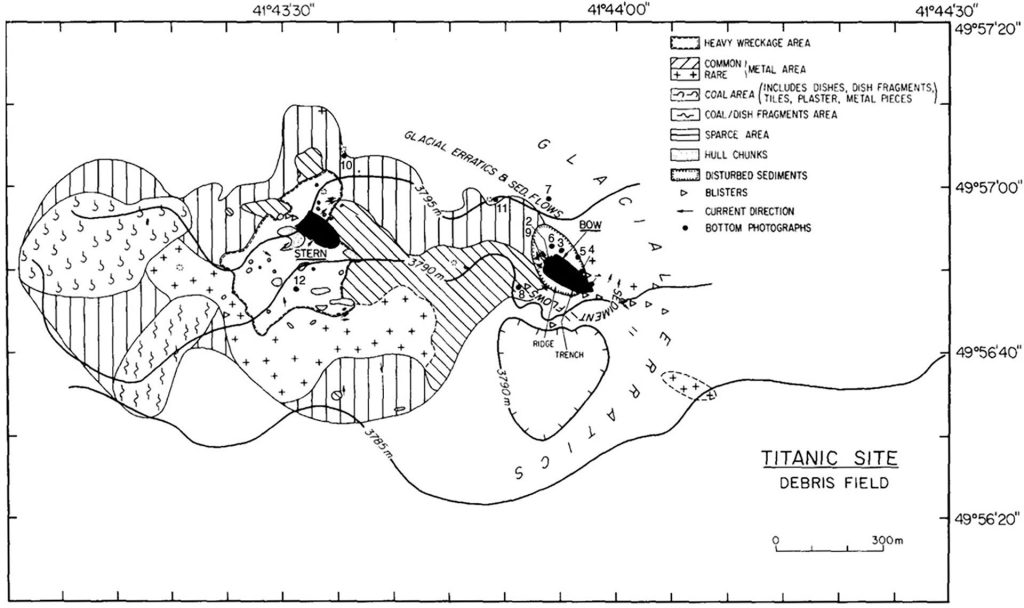

The image above – courtesy of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution – was drawn by Ballard and his team as they plotted the debris and largest objects within the field. The bow (ship’s front end) and stern (ship’s rear end) are clearly indicated by the large black shapes. Notice anything about the surrounding field?

It’s not symmetrical.

What Ballard realized (due to some previous experience we’ll get to below) is that the underwater currents move the lighter debris – coal, furniture, dishes – away as they drift down to the ocean floor. The heavier objects – large ship pieces such as boilers, the stem, and the stern – tend to drop where they are less affected by currents.

An analogy for a plane crash is once the plane hits, the lighter stuff gets blown all about based on the vector of the plane, but the impact point is most readily identified (large smoking crater, for example). Airplane crash sites are visible from the air when rescue helicopters seek out the accident site and debris. For underwater shipwrecks, there’s no such help available due to the physics of being nearly 3 miles underwater… in the dark.

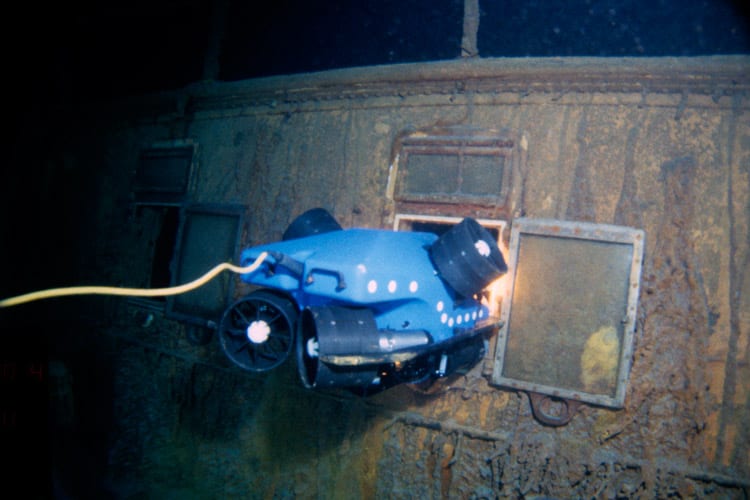

While the French scientists on the Titanic team – aboard the Le Suroit – were using newer synthetic aperture radar (SAR) technology, the U.S. team used video and photographic sleds. The uneven ocean floor made SAR returns spotty, but they could cover larger swaths. The U.S. used Argo (video) and Angus (photographic) sleds, but were limited in coverage to what could be seen by the cameras.

Ballard’s joint team used the last known (or suspected) location of Titanic, beginning where the lifeboats were picked up by the the currents to where lifeboats were picked up by the RMS Carpathia. Working their way eastward, both teams used their tech to look for debris from the ship.

Why? To analyze this question, we must rewind the clock to roughly a month earlier when Ballard’s U.S. team left port.

The savvy explorer he is, Dr. Ballard knew it would take still-unrealized technology to search for Titanic. In his role as a U.S. naval officer, he pushed the limits of ocean exploration with the high tech machines available at the time, namely manned submersibles. But realizing that manned craft kept large portions of the ocean out of reach, Ballard and his Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute (WHOI) team began developing robotic underwater machines that operated using telepresence.

High tech costs high amounts of money, so Ballard petitioned the U.S. Navy to fund his research and development costs. Never one to give anything for free, the U.S. Navy complied, but with a request that Ballard and his team take the new machines on underwater surveys of two sunken U.S. submarines, the U.S.S. Thresher (SSN-593) and U.S.S. Scorpion (SSN-589), lost in 1963 and 1968 respectively. Both boats were nuclear powered, and Naval analysts wanted information possible radioactive leakage from the reactors.

The USS Thresher sank during deep-dive tests approximately 220 miles from Cape Cod, Massachusetts and its final resting place was known by at least late June 1964, visited by the bathyscape Trieste II in September.

The USS Scorpion’s wreckage was found by the end of October 1968, with the Trieste II visiting the site in summer 1969.

Ballard’s desire to search for Titanic gave the U.S. Navy a perfect cover story, while the earlier searches gave his team time to test out the equipment before looking for the shipwreck.

While photographing the Scorpion wreck site, Ballard and his team tracked the debris field around the sub’s crushed hull and came to the conclusion that heavier items from the accident fell closest to the large pieces, while lighter debris pieces were found further away based on currents and fluid dynamics of items falling underwater. Ballard’s “A-ha!” realization during the Titanic search was based on research as well as experience gained from the previous month’s surveys of Scorpion and Thresher.

During today’s 40th anniversary of Titanic‘ s discovery, none of the above is new. Dr. Ballard has spoken… not at length, but snippets here-and-there… about the Titanic search as a cover for the Scorpion and Thresher surveys in the last two decades.

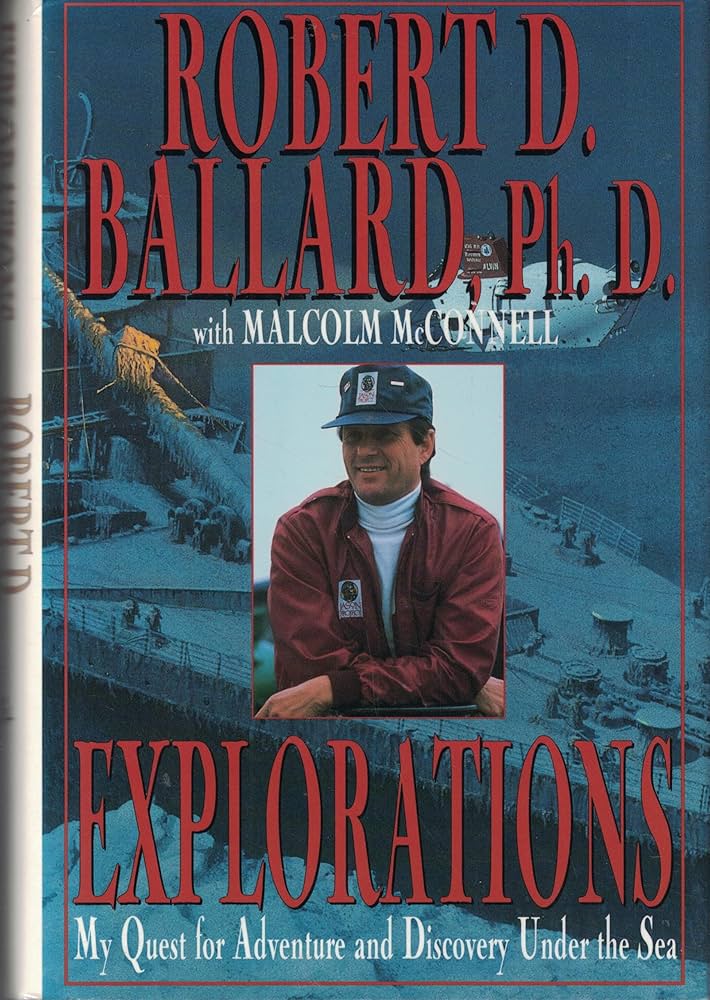

What got me… as my “Duh!” moment, is Ballard writing about all of this in his 1995 memoir Explorations. Inside he outlines his career, Project FAMOUS, and his 1985 search for Titanic… while telling about the U.S. Navy’s request for the wreck surveys of the two submarines. I read his first memoir when it came out in the mid-1990s, but completely glossed over the sub surveys, hungry for more info on the “Rusty Old Boat” (his mother’s words, and I mean no disrespect when I use them here) and his discovery of the Nazi battleship Bismarck.

Talk about a secret in plain sight.

Whew. A lot to write today. The above cloak-and-dagger – ness of the Titanic search, along with the cool, new (for the day) technology developed to search dangerous environments…the amount chemistry, physics, navigation, and just plain common sense needed to run a survey… er… expedition to find “lost things” on the ocean floor.

Its enough to excite just about anyone with a modicum of interest in this stuff*, or similar explorations in other mediums of exploration.

One day I hope a screenwriter tells the “behind the scenes” tale of the Titanic search – I know it may lack Kate Winslet flying with Leo DiCaprio on the bow of a ship… or making out in the car inside the ship… or anywhere else they may have “did it.” But there’s enough emotion and humanistic stories from the Summer of 1985 within to entertain an audience for at least 90 minutes, especially considering the crap on streaming video this year.